Now that you know Luciano Berio and Italo Calvino, let's move on and talk about La Vera Storia. Let's start from basics: La Vera Storia is strictly related to Il Trovatore. In fact, the plot of the first act shows us both what in Il Trovatore is represented on scene (two men fight because they love the same woman) and what in Il Trovatore is not represented on scene but is only told by Azucena and Ferrando.

1. Act 1: the story of Ada and Ugo

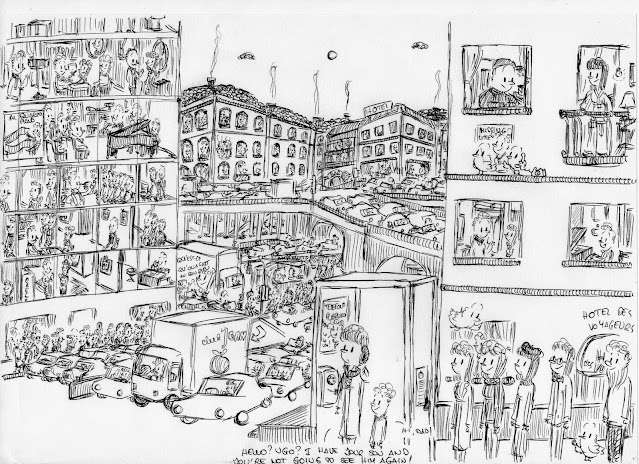

So, let's see what happens during the first act. When the curtain opens, we are in a square in a town in Southern Italy. It's feast day and all the people are happy; there's a brass band playing and everything seems to be going well.

...and they execute him, as you cannot see in the following image (sorry, the scene was too violent. But here below you can see some people having a nice party during the popular feast).

What happens right now? It is very easy: Ada, the executed man's daughter (to be fair, Calvino in the libretto write that she could be his daughter, giving to this a certain degree of uncertainty, while Berio writes in the score that she is the executed man's daughter, showing this relationship to be certain) abducts the son of Ugo, who is the Governor of the Town and who she thinks is responsible for her father's death. So, she takes Ugo's son away and takes him to the big tentacular city...

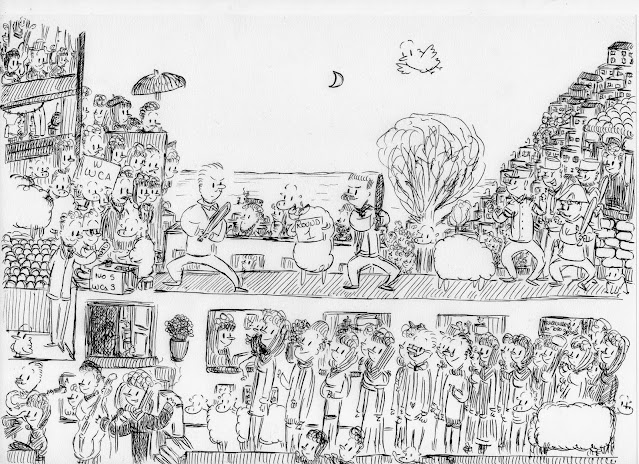

Now, after the abduction of Ugo's son, a cantastoria enters and sings a Ballad. It is the first of six Ballads the cantastoria will sing during the first act: the six ballads comment what's happening on scene and have a musical style which can be archaic, modern or popular. In the first representation of La Vera Storia, the cantastoria was interpreted by the famous Italian pop singer Milva and in the following video we can see her singing the first Ballad from La Vera Storia. In this Ballad, the cantastoria explains why Ada decided to abduct Ugo's son:

We've already said that Berio was very interested in popular traditions and that's why one of the characters in this opera is a cantastoria, who sometimes enters and sing a ballad to comment what happened on scene. Do you know what a cantastoria is? Cantastorie were, in Southern Italy (but we can find them also elsewhere, for instance in the Balkans), popular storytellers who went in towns and villages and there told stories and sang songs about various subjects: love, death, heroes of the Carolingian cycle (let's think for instance about Sicilian Opera dei Pupi) and about events which had recently happened in the region or in the country (for instance, there are many Cantastorie songs which speak about bandits in Southern Italy in the second half of 1800). So, they both entertained and informed about various subjects the audience who listened to them during the feasts.

Berio puts this form of popular storytelling in his opera and makes a pop singer play the cantastoria: this creates an opera in which two worlds coexist and interact. In fact, we have:

1) The world of the "characters" (Ada, Ugo, the condemned to death, the choir and the other characters we'll meet later): the characters act on scene and are the protagonists of what's happening. They are interpreted by "traditional" opera singers, even though Berio make those singers use their voices in lots of different and sometimes uncommon and not-so-traditional ways: he make them sing, he make them talk, he make them use sprechgesang and so on. Do you remember when we talked about Berio's interest for voice and ways of singing? Well, in La Vera Storia we can see an example of that.

2) The world of "narration", which is represented by the cantastoria (to be fair, there are two cantastorie): the cantastoria does not take part to what happen on scene, but comment, repete or tell in a poetic way what's going on. What's more, the cantastoria, as we've already said, is not interpreted by a traditional opera singer but by a pop singer.

But now let's move on...

After the abduction of his son, Ugo dies of sorrow...

...and his other son Ivo takes his place, promising to avenge him.

Now Ivo is in hospital and Luca is in jail, while Little Ugo joined a populist movement and is candidate for MP in general elections (ok, I made the last point up).Berio puts this form of popular storytelling in his opera and makes a pop singer play the cantastoria: this creates an opera in which two worlds coexist and interact. In fact, we have:

1) The world of the "characters" (Ada, Ugo, the condemned to death, the choir and the other characters we'll meet later): the characters act on scene and are the protagonists of what's happening. They are interpreted by "traditional" opera singers, even though Berio make those singers use their voices in lots of different and sometimes uncommon and not-so-traditional ways: he make them sing, he make them talk, he make them use sprechgesang and so on. Do you remember when we talked about Berio's interest for voice and ways of singing? Well, in La Vera Storia we can see an example of that.

2) The world of "narration", which is represented by the cantastoria (to be fair, there are two cantastorie): the cantastoria does not take part to what happen on scene, but comment, repete or tell in a poetic way what's going on. What's more, the cantastoria, as we've already said, is not interpreted by a traditional opera singer but by a pop singer.

But now let's move on...

After the abduction of his son, Ugo dies of sorrow...

2. Act 1: the story of Ivo, Luca and Leonora

What follows is very simple: Ivo falls in love with Leonora, who is loved by Luca as well. The two men quickly begin to struggle for Leonora's love and Ivo is supported by the police, while Luca is supported by the people. Luca and Ivo fight a duel...

...and Ivo gets wounded and Luca is arrested and condemned to death.

3. "La Vera Storia" and "Il Trovatore": two operas on narration

Now that we've talked about Act I, we'll make what you all expect us to do...

...and we won't talk about Act II. Oh, you'll say, that's nonsense! Let us now what happen in act II, come on! Well, actually, that's the problem: in act II nothing happens. Act II is simply a re-elaboration of musical and textual materials which have already been used in Act I. In other words, in Act II we listen to the same music and words we've listened to in Act I, but put in a different order and with changes and cuts.

Act II is, as Berio said, a repetition or a parody of Act I and this is proved also by the fact that, if we go and read the libretto, we discover that there's no libretto for act two; instead, there is a table in which Berio writes in what scene of Act II we'll find the texts and the musical pieces we've heard in Act I. The table, for those who are interested, is this:

What does this mean? Basicly, that Act I and Act II tell the same story, with (almost) the same words and (almost) the same music. What changes is simply the way in which the story is told: in Act I, the facts are shown on scene in chronological order, in Act II they are shown in a more chaotic order, as if the story was set in a dream.

Why does Berio do that?

To understand that, we should go back to where we started, which is Il Trovatore's narrative polyphony. In fact, Berio writes that Act I and Act II talk about the same story in two different ways

as if two cantastorie told two different stories about the same event.

Does it remind you of something? Where have we listened to two people telling in two different ways the same story? Of course: it was in Il Trovatore! There, both Azucena and Ferrando told the story of Azucena's mother death and of the abduction of Count of Luna's son, but they told it in a very different way.

It is not a casual relationship: in fact, as you've probably noticed by reading the plot of act I, La Vera Storia and Il Trovatore tell exactly the same story. The difference between the two operas is simply that in La Vera Storia we can see on scene two events which in Il Trovatore are only told by some characters and never shown on scene:

And, as in Il Trovatore we may ask what's the true story, whether it is Ferrando's one or Azucena's one, so Berio asked, in his Author's note, whether in La Vera Storia the true story is the one which is told in the first act or the one which is represented in the second act. He wrote:

But where is the true story? In Act I or in Act II? I don't know.

So, La Vera Storia helps us understand more about Il Trovatore: both operas deal with the impossibility of telling completely the truth through narration (and in general through art) and so they try to solve this problem by using multiple narrators and point of views.

Both those two operas feature characters whose role is sometimes to tell what happened and not to take part to the action: in Il Trovatore, we can see that sometimes the action on scene suddenly stops and some characters which are involved in the development of the story tell a story which can speak about a far past, as in Ferrando and Azucena's case, or about something recently happened, as in Manrico's case when he tells about his duel with the Count of Luna. Berio, in La Vera Storia, goes even further: here, there are some characters who have only what we can call the "narrative" function and never take part to the action and some characters who are only part of the action and never stop to tell. Again, what in Verdi was immature is largely developed in Berio's opera, where, as we've already said, we have a separation between the world of the characters who tell and the world of the characters who act.

It would probably excessive to see in this difference between the two operas a different view the two authors had on the role of the narrator: someone who is part of the flow of life in Verdi's case, someone who look to others' lives and tell their stories to other people without taking part to that show of actors who struts and frets their hour upon the stage (as someone sometimes said) which we call life in Berio's case.

We could go on talking for hours about this two great operas. Sadly, we have to stop now, but I'd like you to remember two things, after what we've said:

So, stay tuned and see you soon!

...and we won't talk about Act II. Oh, you'll say, that's nonsense! Let us now what happen in act II, come on! Well, actually, that's the problem: in act II nothing happens. Act II is simply a re-elaboration of musical and textual materials which have already been used in Act I. In other words, in Act II we listen to the same music and words we've listened to in Act I, but put in a different order and with changes and cuts.

Act II is, as Berio said, a repetition or a parody of Act I and this is proved also by the fact that, if we go and read the libretto, we discover that there's no libretto for act two; instead, there is a table in which Berio writes in what scene of Act II we'll find the texts and the musical pieces we've heard in Act I. The table, for those who are interested, is this:

Why does Berio do that?

To understand that, we should go back to where we started, which is Il Trovatore's narrative polyphony. In fact, Berio writes that Act I and Act II talk about the same story in two different ways

as if two cantastorie told two different stories about the same event.

(from Berio's Author's note to La Vera Storia - the full text (in Italian) in avaiable here)

Does it remind you of something? Where have we listened to two people telling in two different ways the same story? Of course: it was in Il Trovatore! There, both Azucena and Ferrando told the story of Azucena's mother death and of the abduction of Count of Luna's son, but they told it in a very different way.

It is not a casual relationship: in fact, as you've probably noticed by reading the plot of act I, La Vera Storia and Il Trovatore tell exactly the same story. The difference between the two operas is simply that in La Vera Storia we can see on scene two events which in Il Trovatore are only told by some characters and never shown on scene:

- the execution of Azucena's mother (who in La Vera Storia is replaced by Ada's father)

- ...and the abduction of the son of the Count of Luna (who in La Vera Storia is replaced by Ugo).

And, as in Il Trovatore we may ask what's the true story, whether it is Ferrando's one or Azucena's one, so Berio asked, in his Author's note, whether in La Vera Storia the true story is the one which is told in the first act or the one which is represented in the second act. He wrote:

But where is the true story? In Act I or in Act II? I don't know.

(ibidem)

And this statement makes the name of Berio's opera (La Vera Storia means "the true story" in Italian) sound a little bit ironic, doesn't it?

Besides, La Vera Storia's title comes from Il Trovatore as well: in fact, in the beginning of Il Trovatore, the soldiers ask Ferrando to tell them about Azucena's mother by telling him:

Besides, La Vera Storia's title comes from Il Trovatore as well: in fact, in the beginning of Il Trovatore, the soldiers ask Ferrando to tell them about Azucena's mother by telling him:

...la vera storia ci narra di Garzìa...

...which means: "Tell us Garzia's true story" (I won't stress again that the story Ferrando will tell after this request won't be the true story, it will simply be his point of view on the story: Azucena will have a different view on the events he speaks about and she will let us know that in the second act of the opera. So, again, you can see here the impossibility of knowing which one of the two stories is the real true story). What's more, lots of Sicilian and in general Southern Italian cantastorie began their stories by telling the audience: "I'll tell you the true story of...", so we can also see the influence of popular narration on the title of this opera.

So, La Vera Storia helps us understand more about Il Trovatore: both operas deal with the impossibility of telling completely the truth through narration (and in general through art) and so they try to solve this problem by using multiple narrators and point of views.

Both those two operas feature characters whose role is sometimes to tell what happened and not to take part to the action: in Il Trovatore, we can see that sometimes the action on scene suddenly stops and some characters which are involved in the development of the story tell a story which can speak about a far past, as in Ferrando and Azucena's case, or about something recently happened, as in Manrico's case when he tells about his duel with the Count of Luna. Berio, in La Vera Storia, goes even further: here, there are some characters who have only what we can call the "narrative" function and never take part to the action and some characters who are only part of the action and never stop to tell. Again, what in Verdi was immature is largely developed in Berio's opera, where, as we've already said, we have a separation between the world of the characters who tell and the world of the characters who act.

It would probably excessive to see in this difference between the two operas a different view the two authors had on the role of the narrator: someone who is part of the flow of life in Verdi's case, someone who look to others' lives and tell their stories to other people without taking part to that show of actors who struts and frets their hour upon the stage (as someone sometimes said) which we call life in Berio's case.

We could go on talking for hours about this two great operas. Sadly, we have to stop now, but I'd like you to remember two things, after what we've said:

- Italian music and Italian opera are not dead after Puccini's death

- Il Trovatore definitely is not simply "a wonderful opera with an idiot libretto". We know that Verdi had very clear in mind what he wanted to do when he wrote it (we can see that for instance by looking at the changes he made to the original plot, which as we know came from Spanish drama El Trovador), so we should treat this opera with a little bit more respect. We should think about Il Trovatore as if it were an opera of Verdi's, which it actually is, and not as if Verdi had written it because he thought: "Oh, you know, I have some wonderful music, let's look for some stupid words to put on that. The audience is so silly and they won't notice the opera is complete nonsense!"

After that, I say you goodbye but don't be afraid: I'll be back soon and we'll talk about Verdi's Rigoletto, about the 5 operas by Verdi you should absolutely listen to and about Beethoven's three Leonore overtures.

So, stay tuned and see you soon!

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento