Some of you probably listened to La Scala's premiere, in december. Some of you were there (lucky guys!), some of you watched it on television as I did. I remember it well: I was sitting in front of my TV with popcorns in my hand waiting for Fidelio to start, but when Barenboim arrived and the opera began, I had a big suprise. In fact, I was waiting the orchestra to play this overture...

...but unfortunately, what came out from the orchestra when they began to play was this:

My first reaction was: Daniel, what are you doing exactly? Why did you change the overture playing Leonore II instead of the actual Fidelio overture? Have you completely gone mad? Then, I stopped worrying and loved the opera. And I loved the overture too, because Leonore II is surely far more beautiful than the actual Fidelio ouverture, which is not exactly one of Beethoven's musical peaks (while Leonore II probably is).

You can see in more detail what happened in the following image. I am the guy on the left, the girl on the right is my sister, who loved the opera and the overture and didn't have any reaction to Baremboim's funny musical choices.

You can see in more detail what happened in the following image. I am the guy on the left, the girl on the right is my sister, who loved the opera and the overture and didn't have any reaction to Baremboim's funny musical choices.

Probably, after having read all this you will have two reactions:

1) Who is this Leonora II you're talking about? Is she your girlfriend or maybe Barenboim's one? Don't worry, guys, you will meet her soon.

2) You're gone mad, my friend! And you're probably right (years and years of double bass playing can have serious effects on mental health): my sister didn't even notice the overture was different and this either didn't affect her judgement on the opera nor she saw the spirit of Beethoven coming to complain for the odd choice of Baremboim.

So, if you want to go on reading be careful: after having known the wonderful story of Beethoven and Leonora, you could have the same shocked reaction I had when you listen to a conductor who, as Baremboim did, decides to replace the original Fidelio overture with Leonore II. Read at your risk, the author of this blog is not responsible for the end of long-lasting relationships after a row on Barenboim's musical choices.

1. Mum, I want to write an opera! - Beethoven and opera

Beethoven wanted to write an opera since 1800, but he had a very small problem: he could not find anywhere a libretto he liked. You know, operas at the time were tragic dramas about heroes and gods of Greek and Latin mithology (as you can see, for instance, in Mozart's Idomeneo, about which we talked here) or very vain comedies about a girl and a boy who were in love but who, for some reasons, could not marry. Nothing very different from today's Hollywood movies about Marvel heroes or boy-meets-girl stuff, indeed.

But Beethoven did not like that: he wanted to write an opera which could express great moral values, an opera which could deal with the universal values of freedom and of the struggle against absolute power. So, he could not stand the comic operas which were liked very much in Vienna at the time and he had the desire to write an opera about less vain subjects. So, he kept on refusing librettoes for years, before finding the right one.

It is not so strange, indeed: in fact, we can see in Romanticism a very radical change in subjects of operas. Operas began to talk about medieval stories (see, for instance, Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor), about devil and witchcraft (as we can see in the first romantic opera ever, Weber's Der Freischütz), about politics (as we can see in Verdi's Don Carlos), so we should not be suprised that an author like Beethoven, who represents the bridge between classical and romantical music, was interested in finding brand new subjects for his musical dramas.

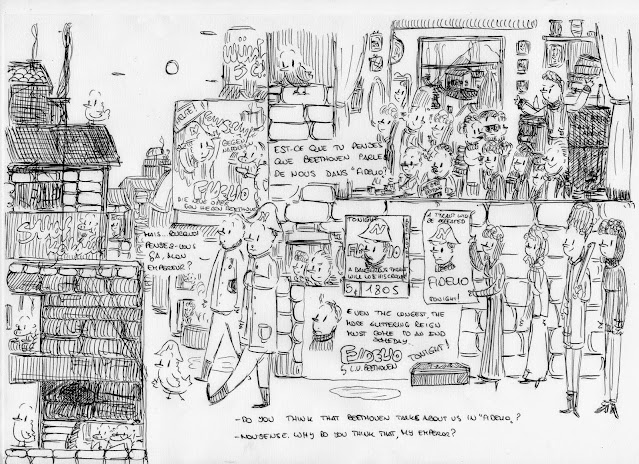

After having read many librettos and having liked none of them, Beethoven at last found what he needed: a French drama which was written in 1794, during the French Revolution, and which talked about freedom and love. Its title was Léonore ou l'amour conjugal (Leonore or the conjugal love) and it was written by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly. We can see his reaction when he found the right libretto in the following image:

Léonore ou l'amour conjugal was a "pièce au sauvetage": what does this mean? The so-called pièces au sauvetage were very popular in France after the Revolution of 1789 and their name explains what they were about: the French expression pièce au sauvetage simply means drama-in-which-someone-is-saved. So, they were dramas and musical operas in which the plot was about a character who was in danger and who at last was saved by someone. That's what happens in Bouilly's Léonore as well: in this drama, Leonore disguises herself as a man and go and work in a prison where she thinks her husband Florestan is imprisoned; she wants to save him and, as we'll see, at last Florestan will be saved.

So, now Beethoven had the plot he wanted: he only had to write the opera...

But Beethoven did not like that: he wanted to write an opera which could express great moral values, an opera which could deal with the universal values of freedom and of the struggle against absolute power. So, he could not stand the comic operas which were liked very much in Vienna at the time and he had the desire to write an opera about less vain subjects. So, he kept on refusing librettoes for years, before finding the right one.

| |

|

It is not so strange, indeed: in fact, we can see in Romanticism a very radical change in subjects of operas. Operas began to talk about medieval stories (see, for instance, Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor), about devil and witchcraft (as we can see in the first romantic opera ever, Weber's Der Freischütz), about politics (as we can see in Verdi's Don Carlos), so we should not be suprised that an author like Beethoven, who represents the bridge between classical and romantical music, was interested in finding brand new subjects for his musical dramas.

After having read many librettos and having liked none of them, Beethoven at last found what he needed: a French drama which was written in 1794, during the French Revolution, and which talked about freedom and love. Its title was Léonore ou l'amour conjugal (Leonore or the conjugal love) and it was written by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly. We can see his reaction when he found the right libretto in the following image:

Léonore ou l'amour conjugal was a "pièce au sauvetage": what does this mean? The so-called pièces au sauvetage were very popular in France after the Revolution of 1789 and their name explains what they were about: the French expression pièce au sauvetage simply means drama-in-which-someone-is-saved. So, they were dramas and musical operas in which the plot was about a character who was in danger and who at last was saved by someone. That's what happens in Bouilly's Léonore as well: in this drama, Leonore disguises herself as a man and go and work in a prison where she thinks her husband Florestan is imprisoned; she wants to save him and, as we'll see, at last Florestan will be saved.

So, now Beethoven had the plot he wanted: he only had to write the opera...

2. Bad luck for Ludwig

...but his problems with his desire to write an opera had only begun.

You know, Beethoven was a perfectionist: he wanted everything to be in the right place in the music he wrote and so he kept on changing things in the musical pieces he was writing until he was completely sure that everything was perfect. But, in Fidelio's case, it was not only his desire to write something perfect which gave him problems: he had also bad luck.

After having chosen the subject of the opera, Ludwig entrusted the librettist Sonnleithner to write the libretto and then wrote the music for the opera. Well, actually, what Beethoven was writing wasn't exactly an opera. It was a Singspiel and Singspiel was a music drama which was different from Italian opera mainly for two things:

- It was sung in German

- In Singspiel we haven't Italian opera Recitatives (if you don't remember what Recitatives are you can read this), which are replaced by spoken dialogues, by parts in which the singers act instead of singing. So, Singspiel was very similar to modern musicals: the characters on scene acted, then sang, then acted again and so on.

Anyway, Beethoven managed to finish his opera and the Singspiel was first represented in Vienna in 1805.

Oh, you know, Beethoven believed very much in this opera: he had put in it all the strong beliefs he had, showing both his desire for freedom and his desire to struggle against the tyrants: Florestan, in Fidelio, is imprisoned for being an enemy to the tyrant Don Pizarro, Leonora, in the end of the Singspiel, points a gun against Don Pizarro and she'd kill him if a man sent by the King of Spain (the opera is set in XVII Century in Spain) didn't come and arrest the tyrant before she could do that. At last, Freedom triumphs, the tyrant is defeated and Florestan is set free!

Wonderful, isn't it?

There was only a little problem: the opera was first represented in Vienna in 1805 and Vienna, in 1805, was occupied by the French army. Napoleon had defeated the Emperor of Austria and so the French boys were in town (and went to theatres). As you may imagine, the French did not like this opera, which talked about freedom and struggle against tyranny, because, for some reasons I really cannot understand, they thought: "Well, in this opera there are two heroes who fight against a tyrant... Is Monsieur Beethoven saying that we are oppressing the Austrian people as Don Pizarro does and that the Austrian people should revolt as Florestan and Leonora do?"

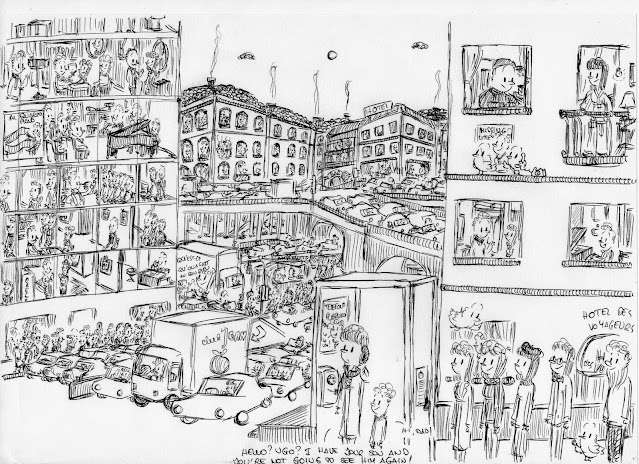

You can imagine what happened: the opera was first represented in a theatre which was full of French soldiers, as you can see in the following image...

...and didn't have success. End of story.

But Beethoven did not like that: he had worked a lot and now everything ended like that? That was nonsense! So, he changed something in the opera and this new version was represented in 1806: now, everything could be fine, the French had went back to France, the opera was brilliant...

| |

|

...but now Beethoven himself didn't like the result and kept on re-writing the opera. It became sort of a hobby: when he had a little free time, instead of doing crosswords, he wrote music for Fidelio. The only problem was that Beethoven didn't have much free time and the final version of the opera was represented only in 1814.

So, if we want to sum up, Beethoven wrote three versions of Fidelio:

- The first version was represented in 1805 in front of an audience composed mainly by French soldiers

- The second version, which is a little bit different from the first, was represented in 1806

- The third version, which is the one which is played today and which is very different from the other two, was first represented in 1814

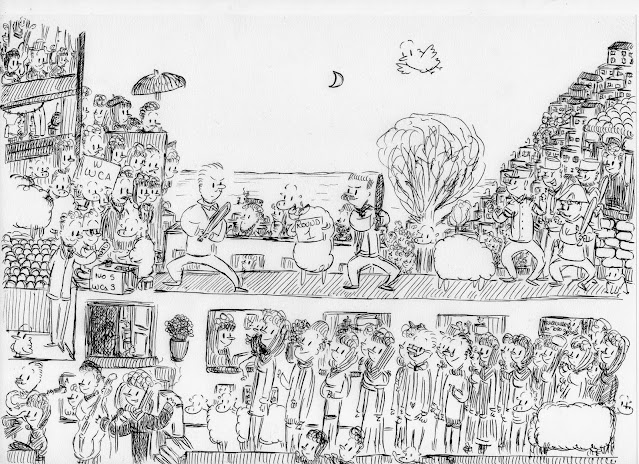

Fidelio didn't have a great success when it was first represented. It was only in the 1820s that the opera became very popular and represented everywhere in Austria and in Germany. Why? Well, like in detective stories what you have to do is to look for the woman, cherchez la femme, as the French say. And the woman, in this case, is a very famous opera singer of the XIX Century: Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient.

Frau Schröder-Devrient is a very important figure in history of music for many reasons: she inspired very much Richard Wagner when he was moving the first steps in the world of opera and she supported him while, in the 1840s, both she and Wagner lived in Dresden: she invited him at her house and, what's more, she sang in the first representation of many Wagner's operas (Rienzi, The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser). Which is quite kind from her part, given that at the time she was a very famous opera singer and Richard Wagner a quite unknown composer who hadn't had success in Paris some years before. The importance of Wilhelmine for Wagner's career is shown by the fact that Wagner, who liked to speak ill of everybody, always expressed a deep respect and gratitude to Schröder-Devrient.

Well, Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient had sung in Fidelio when she was seventeen and she'd liked the opera. So, when she became famous, she began to play Fidelio in all the theatres in Germany and she made the German audience love this opera. Fidelio began to be represented more and more in German theatres and it still is today.

Thank you, Wilhelmine!

Frau Schröder-Devrient is a very important figure in history of music for many reasons: she inspired very much Richard Wagner when he was moving the first steps in the world of opera and she supported him while, in the 1840s, both she and Wagner lived in Dresden: she invited him at her house and, what's more, she sang in the first representation of many Wagner's operas (Rienzi, The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser). Which is quite kind from her part, given that at the time she was a very famous opera singer and Richard Wagner a quite unknown composer who hadn't had success in Paris some years before. The importance of Wilhelmine for Wagner's career is shown by the fact that Wagner, who liked to speak ill of everybody, always expressed a deep respect and gratitude to Schröder-Devrient.

Well, Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient had sung in Fidelio when she was seventeen and she'd liked the opera. So, when she became famous, she began to play Fidelio in all the theatres in Germany and she made the German audience love this opera. Fidelio began to be represented more and more in German theatres and it still is today.

Thank you, Wilhelmine!

3. The three Leonores: back to the beginning!

Now we know everything about Fidelio (well, we haven't talked very much about the plot, but I promise I'll do that in another post) and we can talk about what we were saying in the beginning of this post: we can talk about the three Leonore overtures.

We've said that Beethoven wrote, re-wrote and re-wrote again Fidelio and one of the things that he didn't like and that he kept on changing was the overture to the opera. In 1805, for the first representation of Fidelio (yes, the representation in front of the French soldiers), he wrote the overture which now is known as Leonora II...

...then, in 1806, for the representation of the second version of the opera, he changed the overture and wrote Leonora III. Wait, wait... and Leonora I? Well, Leonora I was written later, for a representation of Fidelio which had to take place in Prague (and which at last didn't take place).

But Beethoven didn't like the three Leonore overtures and there's a reason for that: they were wonderful, maybe a bit too long but musically stunning, but they had a problem: they revealed to the audience how the opera ended. In order to understand this, I have to make a little spoiler and say what's the end of Fidelio: in the end of Fidelio, Leonore, who until now has been disguised as a man, reveals her real identity and saves Florestan from death by pointing a gun against Don Pizarro, the governor of the prison. She'd probably kill him but suddenly...

...the trumpet plays and a man sent by the king of Spain arrives, sets Florestan free and arrests Don Pizarro.

Well, all three Leonore overtures have in the end this here-come-the-goodies trumpet sound. So, from the very beginning of the opera you know that in the end the man sent by the king of Spain will come and set everyone free. Which is not exactly very good, from a theatrical point of view.

So, Beethoven at last decided to write a short overture, which was featured in the 1814 version of Fidelio and which is the one we can listen to nowadays. The three Leonore overtures continued and still continue to be played in concerts, since they're really beautiful. Mahler used to play Leonore III before Fidelio's act II and many conductors did that after him, even if this tradition is less followed today.

So, can you understand now what was my problem with Baremboim's choice? He used Leonore II instead of the traditional Fidelio overture, but Beethoven himself had rejected Leonore II as an overture to Fidelio and had decided to replace it with the overture we can listen to nowadays!

But, after all, Fidelio is a wonderful opera and I hope you'll go and listen to it. I will write again soon and we'll talk about the operas of Verdi you should absolutely listen to.

See you soon!